Chava Rosenfarb was born in Lodz in 1923 to parents enmeshed in the life of the Bund, a political and social justice movement that flourished in interwar Poland. In contrast to Zionists, Bundists believed that Europe could and should remain central to the future of Jewish life. Economically, they embraced socialism. (Bundism thrived in the highly Jewish, highly urbanized cities of Poland, especially Lodz, a center of textile manufacturing regularly compared to Manchester.) Linguistically, they championed Yiddish over Polish or the Hebrew that Zionists, aimed to resurrect. Spiritually, they turned Judaism’s emphasis on reparation (the messiah will not arrive until we have perfected the world) to social justice ends in their own community.

Like every other Jew her age in Poland, Rosenfarb’s education was interrupted when Germany invaded in September 1939. A few months later, she was interned with her family in Lodz’s sealed ghetto. Amazingly, she, her sister, and her parents remained together until the final liquidation of the ghetto in the late summer of 1944. Along with some friends, the family had prepared a hidden space in their apartment building; more than 20 people crammed into it in those final days. Although they escaped notice for more than three days, their luck eventually ran out and they were deported to Auschwitz. Rosenfarb’s father was separated from them at the ramp: they never saw him again; she would later learn that he died in an allied bombing raid in Germany in the last days of the war. The Rosenfarb women were sent to Sasel, a work site in a Hamburg suburb, where they rebuilt roads for several hard and cold months. Early in 1945 they were deported again, this time to Bergen-Belsen, where Rosenfarb, sick from the typhus infestation that swept that notoriously chaotic place (all camps were disaster zones in the last weeks of the war: the situation in Belsen was perhaps the most terrible of all), clung to life, more dead than alive, when the camp was liberated in April.

Remarkable experiences as a DP and an illegal alien in Belgium followed; by 1950 the Rosenfarbs, along with a man Chava had known in Lodz, reencountered in the ruins of postwar Germany, and later married, secured visas to Canada. (That man, Henry Morgenthaler would later champion the cause of legal abortion in Canada, becoming, in my 1980s childhood, a figure equally reviled and admired. My mind exploded when I learned this connection.) The refugees settled in Montreal, where Rosenfarb would spend most of the rest of her life. In this new world, along with caring for her mother and raising her children, Rosenfarb continued the writing she had begun in the Lodz ghetto. After poems came novels and short stories, her efforts culminating in her three-volume fictional chronicle of the Lodz Ghettto, The Tree of Life (1972, translated into English by her daughter, Goldie Morgenthaler).

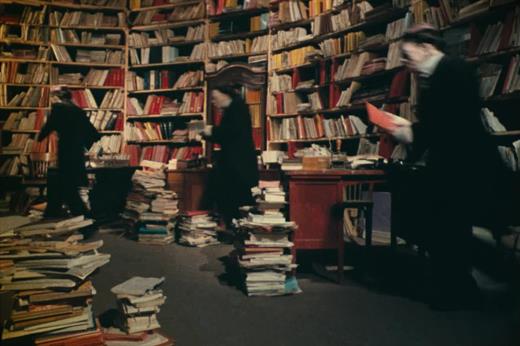

I learned all this and more in a wonderful course offered by the Yiddish Book Center, spurred by the publication of her collected short stories (excellent, especially the dramatic “Edgia’s Revenge,” which I immediately added to my syllabus). The Center offers courses and talks regularly; check them out if you have any interest in all things Yiddish.

Rebecca Donner, All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days (2021)

Mildred Harnack née Fish grew up in Milwaukee to an intermittently employed father and a mother who was a stenographer. In the 1920s she attended the University of Wisconsin, where she met Arvid Harnack, an economist and jurist from Germany who could, unlike any man she had met before, match her as much in the seminar room as on the dance floor. By 1929 the young couple—they had married three years earlier—was living together in Berlin. Mildred would return home only a handful more times. Berlin was exciting, even for a poor couple like the Harnacks. All kinds of change seemed possible. But the rise of the Nazi party threatened all that. Mildred was fired from her position teaching American literature in 1932 because of her opposition to the party, even though it would not come to power until the following year. Needing to find work, Mildred took a job teaching working class students at night school. She loved her students, believed in their ability to transform their lives, and eventually recruited some of them as central figures in a resistance movement that she and her husband began building in the early years of the regime. The circle, as she called it, met to share ideas, often over book discussions, and distributed leaflets denouncing Nazi policies. It was loosely aligned with other resistance movements, including the one that included the pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a cousin of Arvid’s, and the one led by Harro Schulze-Boysen and Libertas Haas-Heye, which eventually led Arvid to pass on military secrets he gained from his work in the Reich Ministry of Economics. Rebecca Donner, who happens to be Mildred’s great-great-nice, tells the story with flair and sympathy.

I found it fascinating to compare Donner’s book to Norman Ohler’s Bohemians, in which Mildred is a bit player. Donner has much less sympathy with Haas-Heye than Ohler does—which makes sense since Haas-Heye ratted Harnack and the others in the so-called Red Chapel group out. It seems she was duped by a supposedly sympathetic secretary in the jail where she was held in custody—but duped rather easily, Donner implies.

Earlier in the 1930s, Mildred befriended Martha Dodd, daughter of the US ambassador. When Dodd was replaced, she became close to the wife of the new First Secretary, whose son, nine-year-old Don Heath, Jr., acted as a courier, carrying clips of paper in his backpack from his English lessons with Mildred (whom he adored) to his father. Typically, those messages consisted only of a time and place where Mildred or Arvid could meet with Heath to pass on information in person.

This work was dangerous, of course, and it some sense it was only a matter of time before she and Arvid were found out. Had the group’s Soviet handler not been so clumsy, they may have escaped detection. When they realized their cover had been blown in September 1942, the couple tried to get to Sweden, but they were arrested in East Prussia the day before they were to set sail. Mildred’s initial six-year prison sentence was overturned by Hitler himself. A new trial sentenced her to death; she was executed by guillotine in February 1943.

As its title implies, nothing is comforting about the subject matter of All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days. It’s a sad book. In her final days Harnack was miserable: eaten by lice, beaten by guards, almost unable to speak to the fellow prisoners who admired her. But grief and despair shadowed her long before her arrest; I was moved by the cost of Harnack’s convictions. Her commitment—compounded by her inability to say anything, lest it further endanger her—destroyed her relationships with almost everyone, especially her American family. By the end, Harnack has the remarkable but unenviable distance from the world of someone like Simone Weil. Donner admires her great-great-aunt, and makes us admire her, too. But she has the guts to admit that principled resistance to injustice can lead to the calcification of so much that is human. How painful to see the erosion of that Wisconsin college girl, wide-eyed and full of the desire to teach and to learn, in love with a man and the world. How loving and patient of Donner to have resurrected her.

[An aside: Donner relies heavily on William Shirer’s diaries. That surprised me: he seems so old-fashioned. Who reads The Rise and Fall of the Nazis anymore? But Donner knows what she’s doing: based these excerpts, he was a hell of a writer.]

Emily Tesh, Some Desperate Glory (2023)

The always reliable Adam Roberts tipped me on to this in his annual sff recap in The Guardian. Then Ian Mond praised it too. The Venn diagram of their tastes is close to being a circle, but everything in it is top-notch. Roberts calls Some Desperate Glory “a blend of space opera and military SF that refreshes both modes,” which sounds exactly right to me, even if I still don’t quite know what those terms mean.

Kyr has come of age on Gaea Station, the last redoubt of humanity after earth is destroyed by alien species who have decided that humans are irredeemably violent. (I mean, not wrong.) Her seventeen years have been marked by submission, dedication, and toughness, to others but above all to one’s self. Food is fuel; rest mandated so the machinery of the body and the station can keep going; families are split apart, the children, bred to emphasize traits necessary for survival, are raised in same-sex age cohorts after they leave the nursey.

Gaea, it becomes clear, is Sparta.

And Kyr loves it.

Along with her twin brother, she is the best of the best: fast, strong, smart, zealous, loyal to the cause. Yes, her “siblings” hate her—she’s always ratting them out and pushing them to exhausted, shameful tears—but such toughness is needed for humanity to enact its revenge. As the date of her cohort’s graduation approaches, Kyr can’t wait for her assignment. She knows she’ll be named to the warrior caste. And then she’ll be able to throw off her only black mark: a family history of treachery. Ten years earlier, her older sister fled the station with her infant child, probably for a planet where the aliens let humans live on sufferance, symbolically neutered, as pathetic as lap dogs. When Kyr’s assignment comes back all wrong—her shock compounded by the news that her brother has been selected for an even more prestigious, albeit suicidal mission—she hatches a plot to follow him. The journey will eventually revise her entire sense of the universe.

I admired Tesh’s accomplishment here: she lets us to read against Kyr (we know she’s more than insufferable: the perfect fascist, really) even as we can understand her zeal for her embattled mission. (I say “we” but a quick glance at Goodreads—I remembered why I never do that—shows me that Tesh’s skill with POV is lost on some readers…) In a brief afterword, Tesh lists some of the works she consulted in writing Some Desperate Glory: books on North Korea, Paxton’s classic study of fascism, and Lawrence’s Wright expose of the handful of people who have escaped scientology. All of which allows her to pull off her greatest trick: like Kyr, readers too are deprogrammed, the “facts” of the novel’s world cast into new light as we proceed. An unpredictable quest story follows, with plenty of plot twists and heart-in-mouth moments. (I was on the verge of tears by the end.) Queer love stories, found families, alternate realities: all the things contemporary sff is known for come into play. Good stuff.

Walter Kempowski, Marrow and Bone (1992) Trans. Charlotte Collins (2018)

I raved about this writer last month.

Marrow and Bone might be the least terrific of the three Kempowskis I’ve now read, but it’s still very good. (Don’t start here, though.) Jonathan Fabrizius is a freelance writer who, thanks to a small stipend from an uncle, lives in charming modesty in 1980s Hamburg, sharing one of those impossible German apartments (carved up willy-nilly from a grander space, bathrooms in the hall, no kitchen to speak of) with a girlfriend who has given up on him. Out of the blue, an invitation comes from, of all things, the organizers of a road rally across the former East Prussia: they want Jonathan to write about the sights attendees might enjoy as they follow the racers from east to west. Jonathan accepts with alacrity: he needs the money, but he also has ties to the region. His companions are a former racecar driver and a representative of the event organizers. Like all picaresques, Marrow and Bone shambles from one incident to another, most of which at first seem consequential, even dire, but prove to be irritants at worst, spurs to further discoveries at best. (When their car and luggage is stolen, for example, the company immediately sends another car, and the protagonists later find the luggage abandoned by the side of the road.) Jonathan, a bit of a schlemiel, need never worry about the consequences of his failures: in one moving scene, he promises to mail form the West some anxiety medication to the mother of a suffering young woman. Tragically, absurdly, he loses the address: he feels bad there’s no way to reach them, but he’s content to throw up his hands.

It’s clear that Kempowski is diagnosing the post-communist situation in this tale of the last days of divided Germany. How so and to what end are harder to say. Maybe that comes from the newness of the events (published only three years after the fall of the wall). Or maybe from Kempowski’s haziness, which can be hard to disentangle from Jonathan’s. Importantly, though, Kempowski does not think it would have been better had the Germans not lost East Prussia. He acknowledges that Poles have had opportunities and made a go of things—even if those things are sometimes muddled in the ordinary way of the world—that they might not have had under German hegemony. But he also laments a lost world—especially the mix of cultures that East Prussia, like all borderlands, once had. He’s similarly gentle with the 1980s leftist intellectual milieu to which Jonathan belongs. He pokes fun at their belief in the power of petitions and protests, but admires their conviction.

I guess I am writing myself into the position that it is not easy to tell what is mild (and therefore, possibly, generous) in the book and what is fuzzy (and therefore, possibly, lazy).

Oliver Burkeman, Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals (2021)

If we’re lucky and live into our seventies, we spend about four thousand weeks in this life. To my numerically-hazy mind that seems lot, but it’s not. And when you’re in your 50s, you can’t help but conclude that you have hardly any weeks left at all. Burkeman’s self-help book for people who cringe at the idea of self-help gently asks us to recognize the fact that we all want to deny, the inescapable reality quantified in his title. Burkeman, a self-professed failed productivity expert, exhorts us to make those weeks count—but not by being more productive. (Some of the most amusing parts of the book concern the various productivity regimes to which he has pled fealty. As he wryly notes, work tends to beget work. Answering email is shit!) The point isn’t that we should spend our time only doing what we want—none of us have that freedom, especially those of us who aren’t independently wealthy. Rather, it’s simply that we should be intentional about our time. But what a huge “simply” that is! It means recognizing our mortality—something that I, for one, have had no interest in doing.

A short, well-written, often funny, and always accessible book (Burkeman makes even Heidegger intelligible), Four Thousand Weeks has kept its hold on me in the weeks since I read it. He demolishes the belief so many of us have that our real life will begin at some indefinite future time: as soon as I do x or figure out y, I’ll finally do z (clean the closets, commit to a relationship, write that book), when in fact our lives are nothing but the cluttered, half-hearted, scattered series of moments that we wrongly think of as garbage time before real meaning will arrive. He argues that our impatience, our “it would be funny if it weren’t so sad” drive to hurry through life, is really a sign of how strongly we deny our mortality. We feel time is wasted because we are reluctant to embrace discomfort and resistance. We don’t have to like traffic jams, checkout lines, or toddler games. But until we learn to experience them as time we will find them even more painful than they are.

Some of you might remember Emma Townsend from Twitter (I miss her). I raised an eye at her when she raved about Four Thousand Weeks; she gently encouraged me not to be so hasty. It took me a while to try the book for myself, but I’m so glad I did. Sorry for doubting you, Emma.

Rebecca West, Harriet Hume (1929)

A witchy book; I must confess, I am not much for witchy things.

West’s strange fantasia of a (non)-relationship over several decades is the subject of Episode 22 of One Bright Book—worth your time, in my opinion, especially if you want to hear smart readers wrestle with a book they don’t quite know what to make of. Fascinating for the contrast between West’s mode here and that of her gigantic Balkan travelogue, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, which I spent some time with each day this month.

I still have a few Rosenfarb stories to read, so I’ll save further comment on the collection for later other than to say how wonderful it is that these are now available in English. If I had more time—and, you know, didn’t spend my days teaching—I’d take classes like this one all the time.

And you? How did you spend January?